Alcohol sale hours by state. Hats off to NV, SC, and LA.

Investigating Democratic Backslide Hungary

Earlier in 2014, I began looking into the causes of the "reforms" in Hungary, which I characterize as a backslide in civil liberties and democratic institutions. I had help translating Hungarian election blogs and polling data from a few dear Hungarians who prefer to remain anonymous. I also interviewed the Current Consul General of Hungary in New York, the former Minister of Development for Hungary, and the former Deputy Head of Strategic Communications for Hungary. The body of the essay - a narrative and empirical look at my four categories of analysis - is very long, but I am happy to share the full project and complete transcriptions of the interviews, if you contact me.

This project evaluates the factors that have amounted to the erosion of democratic institutions and civil liberties in Hungary, which is otherwise modern, in many ways socially progressive, and regionally and internationally connected through the European Union, NATO, and other formal alliances. It examines four levels of analysis to conclude which aspect was the greatest causal factor: economics, politico-structural features, civil society and social attitudes, or individual agency. Determining the relative causality of the factors that have caused a relapse in democratic institutions in Hungary, which was considered a principal successful story of post-Soviet democratic transition, has implications for other incidences of democratic consolidation.

HUNGARY 1990-2014: DEMOCRATIC BACKSLIDE IN PRACTICE

Hungary’s democratic backslide is unique because increasingly conservative and repressive reforms are happening in the same country that fought vigorously for liberalization, democratic institutions, and transparency in 1989.{1} In the summer of 1989, as the Soviet empire fell, Hungarian opposition forces gathered to put pressure against the communist regime. Hungary, arguably the most liberal of the bloc states under communism, had tremendous popular support for free elections and liberalization. Like Czechoslovakia and Slovenia, Hungary adopted parliamentarism because, “[I]n the heat of revolution both citizens and emerging elites reached for the form of noncommunist regime they knew best from their countries’ precommunist pasts.”{2}

The first free elections of 1990 revealed little support for communist leaders, although most people believed that maintaining some continuity in government would have a stabilizing effect. Under this new mixed center-right government, Hungary drafted its first independent constitution, leaving room for adaptation and evolution of the new Hungary. For two decades power shifted back and forth between various parties, most with some communist representation and platforms, but no single party gained enough traction to rewrite the constitution. Liberal reforms occurred gradually, and the country experienced a tremendous economic opening to the rest of Europe. Unlike other bloc countries, Hungary experienced many aspects of liberalization even before its democratic transition. As a result, many analysts believed it would be the most stable and successful case of consolidation in Europe.{3} In 2004, Hungary joined the EU, which some interpreted as a signal that it had completed its democratic experiment.

In 2010, several scandals of corruption in government, most notably the charge that socialist leaders, including the Prime Minister, had disguised the relative bankruptcy of the country, amounted to a national determination for radical change. The Fidesz party, led by Victor Orbán, a reformer since the Soviet period, came to power and implemented dramatic measures. These changes, which can be characterized by a rollback in democratic institutions and civil liberties, were achieved through careful legislation and a massive rewrite of the country’s constitution.

Although the Fidesz party was legally elected to power, its subsequent changes to voting processes have made it extremely difficult for the party to lose a future election. Features such as the elimination of second round voting and turnout requirements have helped to maintain the Fidesz stronghold. In 2010, Fidesz won a legitimate majority (52%), which translated under the old system of representation into a two-thirds supermajority of Parliament (263 of 386 seats). In the 2014 elections, under the new constitution and with new electoral laws, Fidesz was able to maintain its parliamentary two-thirds supermajority, despite having only obtained 45% of the popular vote.

Gerrymandering and other legal tricks have allowed Fidesz to maintain complete control in Parliament. The districts were redrawn in 2010, according to Hungary’s Consul General in New York, Károly Dán, because:

The districts now, if you look at the number of voters for example, this is a much more balanced system then you used to have. The old system was supposed to be around 70,000 [voters per district], but in actuality they varied from 30,000 all the way to 100,000. We inherited these districts from the post-communist era... It’s pretty close [now], it’s about 70,000. This was one of the reasons why the system was changed.{4}

Despite the Consul General’s firm insistence that these changes were made in pursuit of balance, the variation in district sizes is still far more than what is typically accepted as a democratic standard. The Commission for Democracy through Law in the Venice Commission recommends no more than 10% variation in district size,{5} but the Hungarian system varies by 15% of the mean number of voters in each district – allowing substantially more variation (15% both above and below the mean) than the Commission deems appropriate.{6}

In addition to redrawing districts to emphasize votes for Fidesz, the new electoral system has several features that tweak the vote in favor of any large party just enough to maintain a supermajority in Parliament. For example, the new system includes “compensating the winner,” which is the practice of giving the winner of an election the “broken votes” of other smaller, losing parties, to artificially increase the size of the winning party’s mandate. A Budapest newspaper, The Budapest Beacon, calculated that without this practice Fidesz would only have secured 60% of the seats in Parliaments in the 2014 elections, and therefore not enough for a two-thirds supermajority.{7}

Hungarian officials are aware of the advantages that these features give to Fidesz. In an interview after the 2014 elections, former Minister of Development of Hungary Tamás Fellegi stated:

There is one element [of the electoral system] which I personally would never ever think of... that’s compensating the winner. This time, without that, Fidesz would not have had the super majority for sure. This special rule provided the extra four or five votes that they needed. Obviously, technically speaking, this was why Fidesz has a supermajority. I would never ever think of introducing such a measure.{8}

Interestingly, in the same interview, he stated, “I gave a talk recently in Florida, the tile was Villain or Hero. If you read The New York Times, with or without Kim Scheppele, he is a villain. But if you look at the elections results from 2014, I don’t think he is a villain. Who is in the best possible position to make this judgment if not the electorate?”{9} Clearly, some Hungarian officials, while dubious of specific mechanisms of the electoral system, still regard Fidesz’ maintenance of their supermajority in 2014 as a sign of confidence from the electorate.

A two-thirds supermajority in Parliament is sufficient for any number of measures, for example to “declare that the President of the Republic is incapable of fulfilling his or her duties,” (Legal Status of the President of the Republic, Article 12) and to elect new members for the 12-person Constitutional Court (the Constitutional Court – Article 24).{10} A subsequent clause of the Constitutional Court Article states, “Members of the Constitutional Court may not be members of a political party or engage in any political activities,” but when every member of the court is easily hand-selected by a Fidesz majority, the independence of the judiciary from political associations seems comic. In the next six months four judges will retire, and so the two-thirds majority will be a perfect opportunity for Orbán to select individuals who are sympathetic to him.{11}

There are other problematic aspects of the electoral system. In the 2014 elections the International Election Observer Mission of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe concluded that, “The main governing party enjoyed an undue advantage because of restrictive campaign regulations, biased media coverage and campaign activities that blurred the separation between political party and the State.”{12} In addition, by granting citizenship to any ethnic Hungarians living outside of the country, Orbán and Fidesz were able to take advantage of 20,000 more voters, 95% of which (not surprisingly) supported the party.{13} Finally, independent election monitors found that government agencies tasked with supervising the fairness of the election had too many connections to the government itself, and were therefore biased in their assessment.{14}

Apart from electoral system changes, other undemocratic changes since 2010 have included rolling back freedoms of the press, religious and sexual freedoms, and other checks and balances. Minorities must now receive more votes to be represented in Parliament, or even to send a spokesman. Clauses have been added to the constitution that categorically state Hungarian nationalism is Christian – ignoring the many minorities represented within the country. Another clause carefully defines a family as the product of marriage between a man and a woman. The Constitutional Court is enfeebled by the reduction of ombudsmen – public advocates - from four to one, who is now appointed by none other than majority party Fidesz leadership.

In effect, Fidesz has created an extreme majoritarian system through heavy gerrymandering and other institutions such as “compensating the winner.” Hungarian officials justify the translation of the 2014 45% popular vote into a two-thirds majority in Parliament as an anomaly of a new and developing system, for example Ambassador Dán explains,

Right now, yes, 45% [of the popular vote] is enough [for a supermajority in Parliament]. But in ten years, it is not going to be enough, because you’ll have districts that are going to be leaning this way or that way... Getting a certain percent is only one thing – that’s just half of the seats. The other half comes from winning individual districts.{15}

The Hungarian explanation conveniently forgets that individual districts were redrawn precisely to distribute and maximize Fidesz support. These changes, in sum, solidify that the Fidesz party, under president Victor Orbán’s leadership, will be extraordinarily difficult to overcome in any future election, while minority rights continue to wane and an independent judiciary is replaced with hand-selected Fidesz supporters. Fidesz likely would have won a simple majority in Parliament regardless of its new electoral system, but their carefully engineered system has allowed a vastly disproportionate representation. It is no surprise that the 2014 elections went to Fidesz, which has claimed this fact as evidence of popular confidence in the direction that Hungary is moving.

DEMOCRATIC BACKSLIDE IN THEORY

Many scholars have devoted their work to explaining what factors lead to democratization and democratic consolidation. Democratization is the process of a country moving towards democratic institutions and processes, away from authoritarian ones. These works rely on various definitions of democracy. Most have their roots in the work of Robert Dahl, who described democracy as the product of contestation and participation in politics, with free and fair competition for votes.{16} Joseph Schumpeter built on this definition in Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, in which he states, “The democratic method is that institutional arrangement for arriving at political decisions in which individuals acquire the power to decide by means of a competitive struggle for the people’s vote.”{17} This paper will favor a more liberal and demanding definition of democracy, to recognize that any democratic government must have certain commitments to, and protections of, individual freedoms and liberties. This can be expressed through any number of practices and institutions such as checks and balances on government power, fair enforcement of rule of law, protections of minorities, freedoms of speech and press, etc. Most importantly, according to this liberal definition, a democratic government must regard all individuals equally under the law.

Democratic consolidation is the process by which democratic transitions become solidified. This process can be expressed quantitatively, by how long a democratic regime lasts. It can also be expressed qualitatively, by what institutions, social processes, and psychosocial beliefs represent a lasting ingratiation of democratic beliefs and principles. For Linz and Stepan, consolidation involves the development of democratic legitimacy. They conclude, “Essentially, by a ‘consolidated democracy’ we mean a political regime in which democracy as a complex system of institutions, rules, and patterned incentives and disincentives has become, in a phrase, ‘the only game in town.’”{18}

Hungary, like all independent states that emerged from the Soviet bloc, underwent a democratic transition that defies most theories of democratization: rather than experiencing an emergence of revolutionary democratic forces from within, it was lifted free of an external authoritarian power. This paper, however, is not necessarily concerned with what factors contributed to the initial democratization of Hungary. Rather, it seeks to identify what factors prevented successful democratic consolidation, ultimately resulting in the recent authoritarian backslide. The Hungarian transition is also unique from most authoritarian backslides in that the current government received its power through legal processes, rather than hostile takeover. However, Linz and Stepan find that:

[N]o regime should be called a democracy unless its rulers govern democratically. If freely elected executives (no matter what the magnitude of their majority) infringe the constitution, violate the rights of individuals and minorities, impinge upon the legitimate functions of the legislature, and thus fail to rule within the bounds of a state of law, their regimes are not democracies.{19}

For these reasons, despite its legal ascent to power and its strong majority, the Fidesz party under Orbán can still be considered undemocratic.

Dankwart Rustow groups scholars who have written about the factors that enable democratic consolidation into three categories.{20} First, there is a body of scholarship that supports modernization theory, which argues that economic development and its results (greater urbanization, education, literacy, and quality of life) are most closely linked to successful democratic consolidation (Lipset, Geddes, Hubert, Rueshmeyer). Some proponents of modernization theory also argue its inverse: that periods of economic decline are closely linked to the erosion of democratic institutions. A second group of theorists have argued that successful democratic consolidation is consistently the result of defining structural features in a regime. These structural features build competition into the social framework by including society and its leaders in politically relevant associations where they are exposed to peaceful processes of conflict and reconciliation (Ljiphart, Gates et al). Finally, a body of scholarship supports the notion that successful democratic consolidation is primarily the result of strong civil society, social agreements, attitudes, and psychological beliefs shared by a population that legitimize democracy. (Almond and Verba, Dahl). This project will examine each of these potentially causal factors in Hungary (economic development, structural features, and civil society) to determine what has prevented Hungary from successfully consolidating. These categories of factors, while comprehensive, are mostly structural and social arguments. For the unique case of Hungary I have added a fourth category of analysis, individual agency, to assess whether or not Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has had a causal role in the reforms.{21}

CONCLUSIONS & LOOKING FORWARD

Economic decline strongly correlates with the erosion of democratic features in Hungary. A comparison to Poland reveals that Hungary suffered disproportionately to its European Union and post-Soviet counterparts, and its return from decline has been slower. While a linear trend in GDP growth since 1980 shows consistent growth, it is likely that sudden and dramatic economic decline in 2006 mobilized existing social grievances and political aspirations. Despite the fact that other factors were important, economic decline provides the most convincing explanation of democratic decline in Hungary in 2010.

Structural weaknesses in post-Soviet Hungarian democracy provided institutional pathways for the elimination of democratic protections. Particularly, structural features that enable a single party to rewrite the constitution, favor large parties, allow a small majority to have disproportionate Parliamentary representation (and therefore drastically alter the political structure by redrawing districts), and under represent minorities, all rendered the pre-2010 Hungarian government inconsistent and democratically weak. These institutions, in sum, enabled the Fidesz party to come to power through entirely legal means, which certainly contributed to the erosion of democratic principles, but structural features alone were not sufficient to cause the relapse. It is also unclear if structural pathways and features were even a necessary condition in democratic backslide, because it is possible that Fidesz would have seized power illegally or through other legally-tricky mechanisms.

Social attitudes and civic culture were well aligned with democratic backslide in Hungary. A population that was disenfranchised from Soviet leadership, searching for unifying elements of national culture and pride, and regularly exposed to radical ring-wing and discriminatory sentiment, was well primed for movement towards authoritarianism. However, these preexisting social sentiments and cultural features were not sufficient to enact changes, elect Fidesz, or gain a majority to rewrite the constitution until 2010 in the post-recession period.

Similarly, Viktor Orbán’s personal agency and political savvy certainly catalyzed Fidesz’s ascent to power, but would not have been sufficient to instigate reform without other economic grievances, structural opportunities and social attitudes. In fact, his attempts at personal power grabs and national reform failed for two decades until economic structural factors opened the pathway for his nationalist rhetoric to be successful.

These changes in Hungary, primarily instigated by economic decline, will have dramatic future effects on party politics in the state and its relationship with the European Union, which has already provided a resolution demanding that Hungary address its concerns with the new constitution. Hungary’s relationship with the European Commission has been strained since September 2006, when then Prime Minister Gyurcsány was recorded lying about the state of the economy and the EU subsequently provided him with their formal support. Outrage that the Commission and EU were taking such a pointed interest in domestic affairs resulted in the first violent protests in Budapest, outside the Parliament building, in fifty years.{58} Hungary, which has been outwardly detached from the EU since the 2006 crisis, generally regards the EU’s interest in Hungarian laws as overwrought, unwelcome, and without precedent. According to Hungarian Consul General Károly Dán:

The European politicians are just equally politicians. They fight for their political future, they fight for their position, what they say is not always in, legal terms, correct or executable... A very small majority of the issues voiced against whatever we did was legally an issue.{59}

Furthermore the Hungarian government exhibits no interest in revaluating its constitution or laws, or heeling to EU criticism:

How could you anticipate any sort of criticism when you have a constitutional majority, and you change your constitution, and you have a European body that absolutely has nothing to do with it? There is a joke from Monty Python: One can never anticipate the Spanish Inquisition.{60}

Fidesz and Orban have not yet created total lasting power for themselves. As Felligi and Dán both pointed out, Fidesz’s ascent to power in 2010 and its maintenance of a majority in 2014 were dependent on the weakness of opposition parties – particularly the illegitimacy of the Socialist party, and subsequent unpopularity of the Democratic Coalition (DK) for its election of the shamed former Prime Minister Gyurcsany. However, the changes to constitution and electoral laws, and government media control, have amounted to a system that makes it exceedingly difficult for an opposition party to gain traction, and statistically favors larger parties for Parliament representation. Ultimately, while most Hungarian politicians recognize that their supermajoritarian system is unique, they reject external involvement in their domestic institutions, and to express good faith in their party leaders. According to Fellegi:

On the one hand, compared to the ideal type of democracy, it is less. But we still have checks and balances, if you read the Hungarian laws. I see why many people say that some of the institutions are not fully democratic, simply because they give more room for individual judgment of the authority itself... without necessarily the proper court control. That’s clear. At the same time, I don’t see it happening.{61}

{1} Brian J. Forest, "Viktor Orbán: Viktator or Visionary?" Diplomatic Courier 5 No. 2 (Spring 2011): 22-24.

{2} Richard D. Anderson, Jr., M. Steven Fish, Stephen E. Hanson, and Philip G. Roeder, Postcommunism and the Theory of Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 90.

{3} Jeffrey Kopstein, “Postcommunist Democracy: Legacies and Outcomes,” Comparative Politics 35 No. 2 (January 2003): 232.

{4} Interview of Károly Dán, Consul General of Hungary in New York, by the author, April 30, 2014, New York City.

{5} “Joint Opinion on the Act on the Elections of Members of Parliament of Hungary,” Venice Commission and OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, adopted by the Council for Democratic Elections, June 14, 2012.

{6} Kim Scheppele, “Hungary, An Election in Question, Part 2,” The New York Times Blog, February 28, 2014.

{7} Richard Field, “Fidesz Would Have Won 60% of Seats in Parliament but for Dubious Practice of Compensating the Winner,” The Budapest Beacon, April 22, 2014.

{8-9} Interview of Tamás Fellegi, former Minister of National Development for Hungary and President of Hungary Initiatives Foundation, by the author, April 29, 2014, New York City.

{10} “Fundamental Law of Hungary: The State.”

{11} Interview of Tamás Fellegi.

{12} “International Election Observation Mission: Hungary – Parliamentary Elections, 6 April 2014, Statement of Preliminary Findings and Conclusions,” Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, Parliamentary Assembly.

{14} Kim Scheppele, “Legal, But Not Fair (Hungary),” The New York Times Blog, April 13, 2014.

{15} Interview of Károly Dán.

{58-60} Ibid.

{61} Interview of Tamás Fellegi.

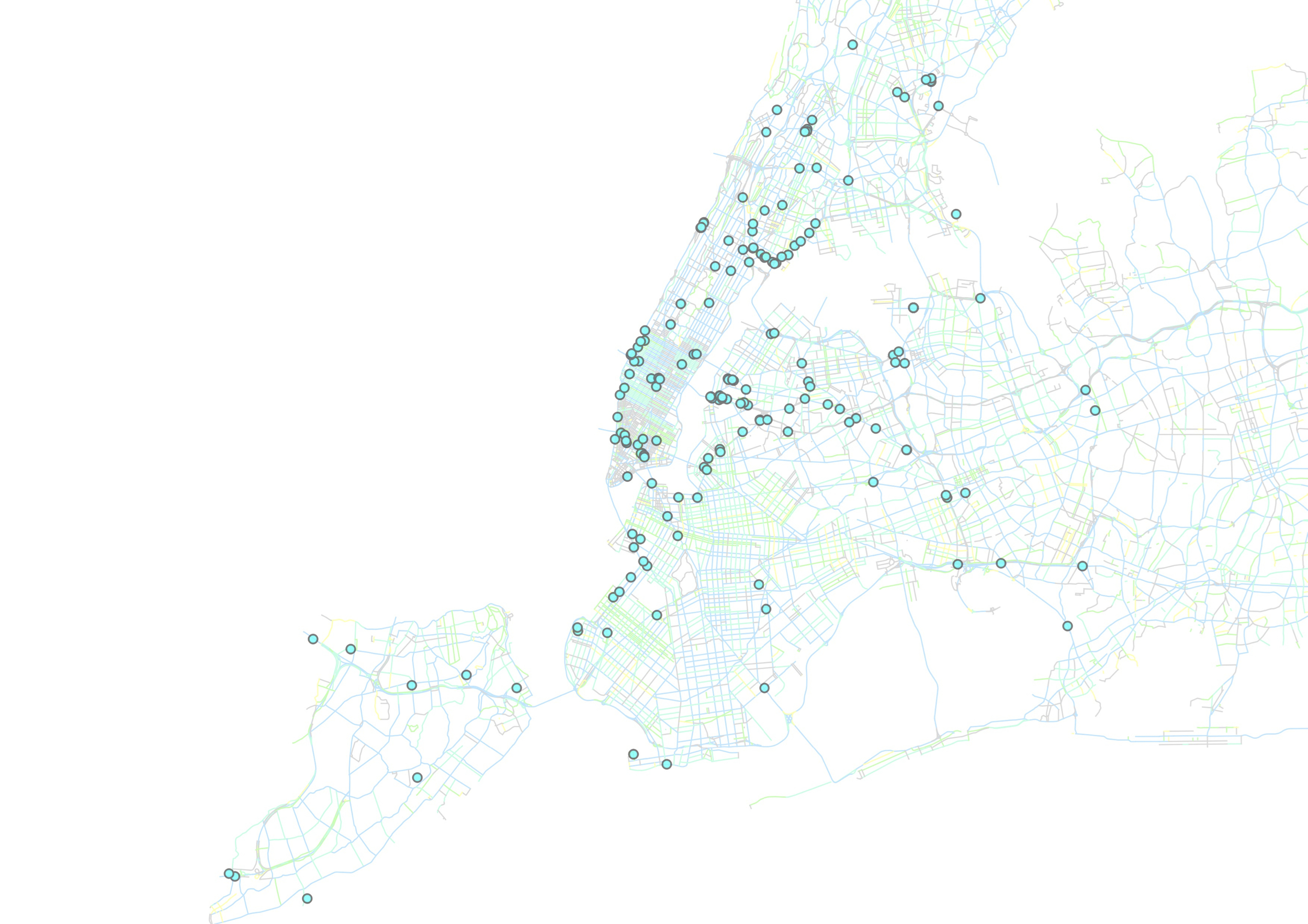

NYC Outdoor Advertising

I've culled a dataset of all of the outdoor advertising in NYC. It's yours for free for any benevolent and non-commercial purposes. Shoot me a message below with a quick write-up of what you want the data for, affirm it's not for commercial purposes, and I'll send it to you. Data displayed over NYC Average Annual Daily Traffic.

Before this street harassment map debacle consumes my whole blog, I want to offer final words. I received two thoughtful and direct emails from Upworthy in regards to my post Upworthy Let Me Down. I tried to summarize, but it feels more honest to just quote the text. I'm including my response as text and not as quoted text because a) I don't want to be painfully redundant and b) a girl only has so many words.

Hi Sarah,

First off: I'm really sorry you felt your work was misrepresented on Upworthy. (I read your blog post and wanted to write you). I can only imagine how frustrating it is while you're trying to illustrate such a rampant social problem. We have that goal in common. So if you don't mind, let me share a bit about how we think about these things at Upworthy, to help shed some light on the stuff you found objectionable in how we promoted your maps.

You're right, we choose thumbnails with a specific purpose in mind: to get attention in the crowded landscape of a social news feed. Internally at Upworthy, we call them eyecatchers. And what our data has shown, after thousands of experiments, is that images like the first one we chose are what tend to catch the most eyes. Our goal is never to be needlessly objectifying or sexualizing, but because we test so many images, we often use stock photos to find facial expressions, body language, etc to match the tone of the headline and the story in the content.

In our use of the word "hottie" in the tweet, the reasoning is similar. We want people who don't think street harassment is a problem, or don't know that it's a problem, to view your work. To do that, we have to get their attention and they have to click through. The goal was not to objectify you or suggest that calling someone a "hottie" is acceptable, our goal is to help people talk to their friends about the content, and often we do that by using language that is accessible to people who wouldn't normally click on a map about street harassment.

We try to be very deliberate in the words and images we use, to find a balance between something that will stand out and catch people's attention in a busy newsfeed without misrepresenting or being disrespectful to the content, because the content won't share if we do that, and our goal is always to frame things in a way our audience will feel comfortable sharing.

And just to say it, the thumbnail and the text used on social media feeds are merely the way we get more people in the door.

No one who clicks through and absorbs your work will remember what image we used to lead them there, or that the tweet used the word "hottie". Instead, they'll remember the quotes on the maps. They'll remember that you were subjected to all that in just three blocks. It's your story that will stick with them. It's your lived experience that will change minds.

We reached out to you because we loved your maps and wanted to help get your work in front of as many people as possible — a wide, across-the-spectrum audience. And the editorial decisions we made were carefully considered in pursuit of that goal.

I do apologize again that the wrong image and Twitter text appeared publicly — I had changed them after my email with you last week, but our audience development team had already scheduled them to go out, and sometimes Facebook or Twitter pull the wrong image even after we change it. Anyone tweeting or sharing the post on Facebook or Twitter now should be seeing the updated text and image.

Best,

—Joe

Hi Joe,

First of all, thank you for taking the time to read my post and respond. I'm grateful that I've gotten several thoughtful responses from Upworthy, and I do understand what happened with image. I do still have some frustrations about how the piece was treated, but all in all, it's valuable to know that you're open to feedback and sincere in your response. I will make sure that my blog reflects that.

Everything you've presented makes sense, and it's fair for the editors to make choices that drive clicks and sharing. My intention isn't to scrutinize every aspect of Upworthy's process, and certainly not to condemn you personally. However, because this is issue is so often confused or dismissed (and because it is so deeply relevant to my life - quite literally daily) I do feel that it's valuable to dive critically into every aspect of how it's presented and discussed.

For Upworthy's purposes - drawing attention from a wide audience to an issue - your presentation was effective and appropriate. For my goal, which is to create an ongoing reflective and nuanced dialog about street harassment- there is more conversation to be had, about what the issue is, and even how we talk about it.

For example, in addition to feelings I shared with you about the image choice, I think it's neither correct or productive to present street harassment as something that only happens to beautiful women or "hotties." Personally, I feel that street harassment has infinitely more to do with asserting power over a person than it has to do with how attractive they are. Moreover, it may even be unfair to present street harassment as a women's issue - there are men, particularly marginalized men, who probably also experience in a way I can't speak to. Again, I'm not an authority on any of this (except when speaking to my own feelings). It may also problematic to conflate street harassment with compliments. Of course there are shades of grey between politely telling a woman that you find her beautiful and accosting her on the street. I know I made a choice to create a map that grouped all of that together to make a point, and again, I'm looking for answers here as much as I'm presenting them.

This is all to say, I see now that Upworthy accomplished its precise goal in this instance, and did it very well. However, the kind of activism that I'm trying to do takes a few more steps to deconstruct every aspect of a social issue and the dialogue about it. I think it's not only fair, but also critical for the advancement of any issue, that we hold each other accountable for the exact words and actions we use about a topic. That's what I tried to accomplish by creating that map, and it was towards that same end that I wrote about the problematic aspects of how it was shared.

For many people who saw the catchy headline and clicked on it, this piece gave them some understanding of the issue and my personal experience, and that is fantastic. For a smaller group of people, who followed the post and then my next blog about the post, this project gave them a deeper understanding of what the practical and discursive issues are at play here. For me, that's a success.

I am grateful for the obvious consideration you have given this, and my hope is that you see us working towards a similar goal.

All the best,

Sarah

Releasing New Data Sets: COPs All Boroughs

Shapefiles generated from NYC Open Data list of City-Owned and Leased Property, combined with MapPLUTO parcel data. If you use these, it would be stellar if you could cite NYC Open Data and me.

Obligatory: Sarah Makes Maps and Sarah Levine are not liable for any deficiencies in the completeness, accuracy, content, or fitness for any particular purpose or use of this or any public data set, or application utilizing such data set, provided by any third party.

Upworthy Let Me Down

tldr;

I set about my street harassment map project to share how my life is filled with disturbingly frequent and banal sexism. By calling women on the street "hotties" - whether or not it was weakly sarcastic - and by deciding that a glamour shot of an attractive woman who could conceivably be me was the best way to market the project - Upworthy simply reinforced that, at the end of the day, my gender and my appearance is what matters most.

When Upworthy reached out about acquiring my street harassment map, I was thrilled. I was assured that it would be attributed in all the right ways, and the writer offered to send me a version to look over before it went live. He gave me superb feedback about how to maximize the exposure by making a Facebook page for myself and building a GIF.

I saw the live post and was, again, enthusiastic, until I looked on the Upworthy homepage and realized that the article thumbnail was, well, not me, my map, or anything related whatsoever to the piece. They selected a stock image of a good looking red head. I wrote the following email to the writer and my contact:

Hi *****,I wanted to share my thoughts with you about a specific aspect of the recent Upworthy piece. I engaged with *an old contact from school* about it - she's an old connection from college - and she encouraged me to share my thoughts with you. I know that many aspects of this are beyond your control, and of course this is not directed to you personally, but I do want to air on the side of transparency.

I am grateful for the affirmation and exposure that the piece has afforded me, and every interaction with you and the rest of the Upworthy team has been lovely. That being said, I was first disappointed, and later disillusioned, when I saw that the thumbnail for the article was not of my map, or anything to do with street harassment or me, but rather a stock photo of what I can only describe as a prettier version of what you know about me.

*My contact* described how your testing schemes inform your thumbnail choices, and how that image performed the best to get traffic. She also explained that Upworthy regularly protects its contributors from harassment by concealing their identity. I have taken those factors into consideration.

I am not upset that the photo wasn't of me. I don't think that would have been appropriate. I also understand that maps as thumbnails are not massively appealing. That being said, I am confused and upset by the choice to use an image that so clearly had nothing to do with the content or message of my work or words. It was not an image of woman experiencing street harassment. It was not an image of a woman on a street. It was not an image of a woman on crutches, or even a woman who is visibly uncomfortable. It's one thing and one thing only: a glamorized and fictional depiction of me.

I understand the balancing act between being true to the content and getting maximum shares. I also understand that to someone who knows nothing about me (i.e. 99.99% of Upworthy) this doesn't alter their perception of the map at all. However, I do feel personally mislead and misrepresented. The editors made a conscious choice to pick someone who could conceivably be me, and more importantly, get a lot of clicks by appearing to be me (red hair and all), without considering that there really is a me, who put herself on the line both in the production and distribution of that map. Moreover, and most importantly, it prioritizes the identity and appearance of a woman over the experience of a woman (...me!), which is what I was trying to highlight in the first place.

I can't help but feel that it was a particularly poor judgment to pair a project about societal perceptions of beauty with an anonymous, unrelated glamour shot.

And all of that aside, the fact that the main draw of the article has nothing to do with its content generally makes me less proud to share it with friends and family, which is extremely disappointing.

I'm still an avid fan of Upworthy, and I think that the process is generally fair and that the mission is deeply important. I do believe that, because of the specific content of this map, this was a poor choice.Sincerely,Sarah

He responded, politely but somewhat dismissively:

I'd be happy to change it to this image: [image] Which scored just as well, if you wish. There's a balancing act when it comes to posting things on Upworthy: things that will get people to look at your map that makes a very important point, and being totally 100% politically correct. Still: you make a good point, and if you'd like, I'll change the image to this.

I asked him to change the image, and it seemed to work:

Until I realized that their effort to correct the mistake (not to mention, acknowledge it) was painfully half-hearted, when I saw that they were still Tweeting my work with a misleading photo:

I have a lot of discomfort with how Upworthy ultimately treated the project. Apart from the total lack of common sense with the thumbnail image, titling the project "If You See a Hottie Walking by..." was extremely off point and underwhelming. My blog post accompanying the final day of the project specifically talks about how it's discouraging and demeaning to be called pet names, or to be called anything at all by a stranger based on your gender and appearance alone. Upworthy chose to manipulate that fact to get clicks from strangers looking for hotties.

I set about my street harassment map project to share how my life is filled with disturbingly frequent and banal sexism. By calling women on the street "hotties" - whether or not it was weakly sarcastic - and by deciding that a glamour shot of an attractive woman who could conceivably be me was the best way to market the project - Upworthy simply reinforced that, at the end of the day, my gender and my appearance is what matters most.

Upworthy's motto is, "Things that matter. Pass them on."

Needless to say, I'm unimpressed.

2.5 Blocks of Street Harassment: Finale

I'm finishing the project after four days. To summarize: After hurting my foot and winding up on crutches, I noticed an increase in comments I was getting on the street. I decided to record and map all the comments I received on my way home from work for the rest of the week.

The map was part whimsical, and part born from frustration. I'm not the first person to talk about street harassment, and this wasn't the first time that I experienced it. Something about being on crutches made the experience more potent, as if I was being targeted specifically, if not deliberately, because I appeared more vulnerable.

The comments I received fell on a wide spectrum. Some were kind, playful, or sympathetic. Others were a bit infantilizing or bordered in offensive or intrusive. Others were clearly sexual, offensive, or even predatory. I've chosen to group them all together for an important reason.

I do not believe that a single man who made any of the comments on my map wished me harm, physically or otherwise. I believe they all had benign intent, and some probably thought they were encouraging me. I believe each man regarded his comments in isolation: as a single, direct interaction. However, pieced together over a 2.5 block commute, over four days of a week, and more, the comments affect me and my thoughts the same way they affect my map: they overwhelm, they disrupt, and they engulf.

There are more issues than simply magnitude. The fact that comments increase when I am limited physically, struggling visibly, and probably looking only at the ground two feet ahead of me, implies that the commenters are encouraged by me being disempowered. Commenting on any aspect of my body - the size of my thighs or the limits of my mobility - reaffirms that either of those are inherently valuable. Comments that are sexually aggressive like "Can I hit that?" and comments that are infantilizing or use pet names like "Baby," "Ma," "sweetie," "or "honey" are clearly motivated by gender, and assert the authority of the speaker over that of the target. Comments that are less hostile, or even apparently friendly, can still be disruptive and intrusive. Taken all together, they're overpowering, distracting, draining, and discouraging.

Most importantly, if I'm thinking about how I look, or how you look at me, or if I am safe around you, then my thoughts are not where I'd like them to be: focused on my day at work and the work left to do. Women who have experienced how verbal harassment can quickly escalate to physical harassment and assault at the hands of a stranger do not have the opportunity to ruminate on emails and data integrations: we are bracing ourselves and our bodies for scrutiny and confrontation.

Pink circle/grey text for Day One, green circle/grey text for Day Two, blue circle/black text for Day Three (pale blue fill for inside BART station).

2.5 Blocks of Street Harassment Part 2

Day Two of my exercise in patience. The second day of recording catcalling while I delicately crutched down 17th Street in Oakland was much quieter than Day One. However, it's undeniable that people on the street are more aggressive when I appear vulnerable. Is it because vulnerability is approachable? Is it because I can't run away? It it because of the irresistible feminine charm of my new hardware?

Pink circle/grey text for Day One, green circle/black text for Day Two.

Highlight of some really supportive and really foul tweets I received in response to Day One:

Stop Street Harassment had some encouraging words.

Random internet troll had some unpleasant words. Apologies for profanity.

I don't mean to condemn any person who makes any unsolicited comment on the street. I also don't mean to condemn these specific individuals for their comments, and I believe all of their intentions were benign. Some of them seemed to have sincere empathy. However, I'm almost certain that all of these men only considered their actions - if at all - in a vacuum. My concern isn't that these individuals are committing singular dastardly acts, but rather that their actions, in sum, render it impossible to make a banal daily commute home without feeling subject to scrutiny based on physical appearance and comportment. At best, it's disruptive, at worst, it's threatening, and either way, it's constant.

It's hard to ignore that these comments are motivated by gender: "Babe," "Sweetie," "Linda," "Honey," "Ma." The choice tweet above clearly is too: "trolling for a rich prince to rescue her." The term male privilege has been so haphazardly used that it feels trite and divisive, but I hope the map reveals that most young women lack the basic privilege of privacy.

See you tomorrow.

2.5 Blocks of Street Harassment

I hurt my foot on Thursday and have been crutching around all weekend. I was struck by the immediate increase in attention I received, as people mistook my new treillage for conversation starters. It was most poignant on my way to work, from SOMA to Oakland via BART. On an average day, I estimate between 0-2 comments on any given commute. This morning I felt comments coming in pairs.

I used my iPhone audio note and my usual geo app to track how many comments were made to me on my way home and where. For the occasional disbeliever, I've mapped the comments below (8 in 2.5 blocks). Paint the scene: I'm hopping along, sweat accumulating, armpits chaffing, and....

Special shout out to "I'll put you in a wheelchair, Ma," because I don't even know if that's creepy or violent or just a judgment on my recovery methods.

Just in case any of these seemed thoughtful or helpful or anything but menacing, some statistics:

- 100% of these comments came from men, completely unsolicited (including eye contact).

- 0% of these men stopped walking to deliver their comments (which might be an indication of some sincere effort to lend a hand), although, to be fair, "Need a lift?" was leaning against his car.

A few lessons learned from Day One of mapping unwanted attention on the street: Popular anti-street harassment campaigns have marketed themselves towards young people in cities - Hollaback is an obvious example. Gentlemen callers #5 and #8, "Let's race" and "Need some help, Red?" respectively, were both apparently normal middle-aged white schmos dressed in business casual with cell phones in hand. There's no just reason for me expect more from these guys, except my gut reaction to men who look like nerdy dads to teenage daughters - i.e. look like my dad - is that they should know better, if anyone ever will. End scene. On to Day Two.

Base data from Alameda Open Data.